Well before I was born, my grandfather, Foster, organized a group of Black business owners against police harassment. Grandpa Foster owned a nightclub in Oklahoma City where police had harassed him and his customers, threatening their safety so frequently that he was forced to close his business. He struggled with providing for our family and eventually turned to alcoholism. I first met my Grandpa Foster when I was 16 years old. He died when I was 19.

I was born to his daughter, Monica, a single mother enlisted in the army who wanted to care for me but was struggling with substance abuse. My mother needed treatment. She was arrested for “paraphernalia” and sent to prison instead. I was 15 years old when I met her.

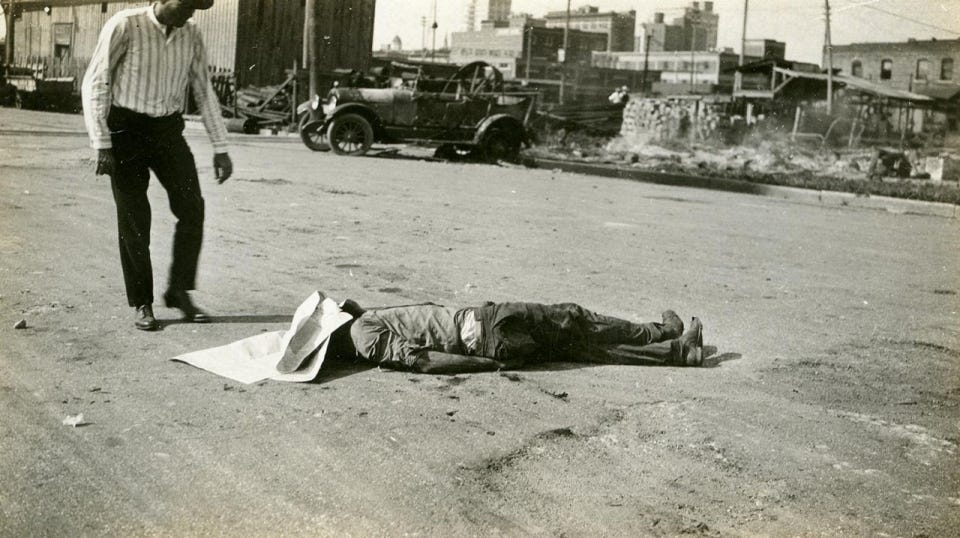

We lived in Oklahoma, where, in 1921 a group of white protesters burned down America’s wealthiest African-American community—the Greenwood District of Tulsa, also known as Black Wall Street. National Guard patrols detained thousands of Black survivors at local fairgrounds and ordered them to clean up the remaining debris.

Dozens were killed. Hundreds were injured. Thousands were left homeless.

I learned before I was five years old that Black people weren’t worth half as much to the police as the paper I’m writing on. Twenty-five years later, police violence continues to shape my life in ways I couldn’t before imagine.

I met my best friend of seven years, growing up in Oklahoma City. When I was kicked out of my (adopted) grandparent’s home at age 15, he ran away with me.

Getting to school was difficult since public transportation was, well, non-existent and because we struggled with not living in one place for longer than a week. Wearing the same clothes to class every day had something to do with it too, I guess.

We eventually dropped out of high school and lived homeless, squatting in abandoned houses for more than a year. It was during this time that I fell in love for the first time.

I fell in love with him, my best friend.

And it was like falling asleep in class: I didn’t mean to, but I did.

It’s remarkable how an empty, two-room shack can feel like a well-furnished apartment when you share it with a person you care about.

We were young at first. So, of course, our relationship had its fair share of naivety. I remember stealing him red roses and cereal from Wal-Mart one night. We ended up, needless to say, spending Valentine’s Day in the juvenile detention center.

Aside from the foolish things we did together — some out of fun, others to stay alive — we founded a place in our life where we accepted who we were and how we loved.

We accepted that we loved.

Over the years, the love of my best friend taught me the importance of loving with my full Self. That meant admitting to him when I was wrong. It meant telling him when I felt overwhelmed and wanted his attention. Most of all, though, it meant allowing him to love me. It meant being vulnerable. His love was radical, unapologetic, and it changed my life.

In 2007, my best friend and partner was killed by the police.

I’ve been in a few relationships since then, all of which have ended in the other person caring more about me than I had for them. That’s because I’m afraid to be open, to be vulnerable again.

I’m afraid to love another man with as much of my Self as I once did and then lose that man to something as routine as a traffic stop.

I’m reminded of Paul D, from Toni Morrison’s Beloved:

“Risky, thought Paul D, very risky. For a used-to-be-slave woman to love anything that much was dangerous, especially if it was her children she had settled on to love. The best thing, he knew, was to love just a little bit, so when they broke its back, or shoved it in a croaker sack, well, maybe you’d have a little love left over for the next one.”

Like slavery, police violence isn’t just oppressive; it’s also pervasive inasmuch as it precludes us from building intimate, meaningful relationships with people we’d otherwise care for deeply.

I can think of three ways police violence especially does this to me.

Impact to Self Worth. Blacks are killed by police at disproportionate and persistently high rates. However, a vast majority of incidents don’t result in the officer being charged with a crime. This teaches me that Black lives are valued less or not at all and are thus less deserving of love.

Impact to Self Preservation. Because I believe that society undervalues Black lives, vulnerability — even if it is the “birthplace of joy”— is not something I practice. For what reason would any person have to be vulnerable in a society where their lives are valued less?

Impact to Self Expression. Without vulnerability, without openness, I stay detached in order to escape the feeling of being worthless. As a result, I miss opportunities to share my life with people that care deeply about me.

Police violence isn’t only impacting our world by the tragic loss of our loved ones. It’s also influencing the way we love others and the way we love ourselves. We are not only fighting for the right to live. We’re fighting for the right to love.

We are fighting for the right to love.